_____________________________________

This is a bogey-man that just wouldn’t go away. The reason is relatively simple. As opposed to the continental (“good”) Western Europeans, the United Kingdom entered the European Economic Community (or Common Market), as it was known in 1973, only reluctantly and only under the duress of an abiding economic and financial crisis. In the now hackneyed phrase attributed to Dean Acheson, US Secretary of State at the height of the Cold War: Britain had lost an empire and was yet to find a role. Would senior membership in Europe become this new role? Why not? Britain’s traditional circle on the international stage, the Commonwealth, was losing its importance and the “Special Relationship” with America only allowed a junior position for a middle-sized European country.

However, as membership solidified, it became evident that even in this early form, the Community felt more than a free trade zone. That some political sovereignty had to be sacrificed. Remember, only 30 years before the United Kingdom had taken the lead in a world war to defeat Nazi Germany and militarist Japan, and had been the centre of a global (albeit stricken) colonial empire on which the “Sun never set”. The vast majority of the Scots, the Welsh and the Northern Irish Protestants (today enjoying ever expanding political and economic autonomy within the UK) had not yet discovered the possibility of life outside the UK. (Irish Catholics had long been able to imagine it.)

Back then, the Labour Party was home to the most important Eurosceptics of the day. Especially the hard Left of the party, focused around the firebrand ex-peer Tony Benn. In their eyes, Europe….. (It is funny how the term “Europe” is used in Britain as a short form for the EEC or EC or EU. After 2004, ten countries in the east would become “part of Europe”. Not before. Nor had the UK been “in Europe” before 1973. Many years after the British entry, someone discovered a rusting metal plaque standing in the water, buffeted by the waves of the English Channel just inside UK territorial waters, with a warning sign: “Beware! You are approaching Europe”)..…in the eyes of the Labour Left, Europe, the EEC, represented big capital, an undemocratic commercial and financial cabal that would eat up, slowly chisel away, British democracy, the hard-earned rights of the individual. They spoke especially on behalf of working class people who had no recourse to private wealth or international networks to protect them. Not only the hard Left of the Labour Party was thinking this way. The Hungarian-born Labour peers, Lord Thomas Balogh and Lord Nicholas Kaldor, economic advisers to the Labour prime minister Harold Wilson, were leading opponents of continued British membership of the EEC on the grounds that it eroded sovereign decision making, made it difficult to protect British jobs and that the institutions of Brussels were not democratic. The effect of membership on immigration was not yet on the agenda.

So it was the Tories under Edward Heath who negotiated the entry into “Europe”, and it was Labour under Wilson who set the first referendum in 1975 on whether to stay in or get out. This, like the fact that it was Mrs Thatcher who negotiated and signed the Single European Act on Britain’s behalf in February 1986 (a year to coincide with the “Big Bang” on the London Stock Exchange) run against the grain of the stereotype that you have to be a dyed-in-the-wool Conservative to be Eurosceptic and that a good working class Labour Party supporting lad would march in the ranks of the “Remainers”.

People who complain about the harsh tones of the current referendum campaign should look at the record of the 1975 (so-called post-legislative) referendum. (There had been no referendum preceding legal entry in 1973.) The language was vociferous and more often populist than not. Mostof the big-hitter newspapers, however, were on the side of staying in the EEC, only the Spectator, the Daily Worker and some local papers aligned themselves with the “Outs”. The result in 1975 was heavy defeat for the leavers: 67% voted Yes, and 33% and said No.

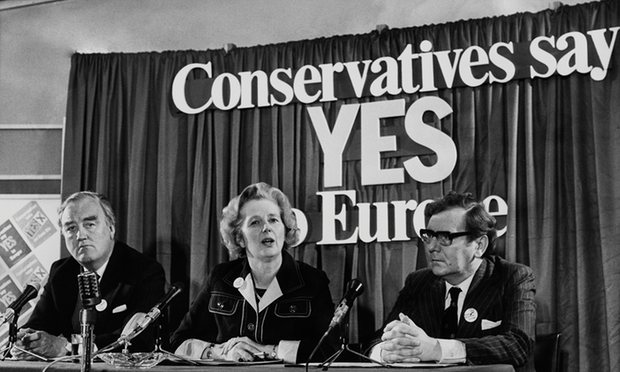

(Source: Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images)

The 1975 referendum campaign. Left to right: William Whitelaw, Chairman of the Conservative Party; Mrs Thatcher, party leader; and Sir Peter Kirk, who led the first Tory delegation to the European Parliament in 1973.

Significantly, Mrs Thatcher, who had just become leader of the Conservative Party, campaigned eloquently for the Yes vote in 1975, citing Britain’s essential economic interests.

But what of today? People quote the daily dose of speeches, announcements and social media postings by both “Leavers” and “Remainers” as the two groups have become known. What is often overlooked is that these pronouncements divide sharply according to whether they are based on emotional (mostly converging on the issue of immigration) or rational (i.e. economic or national security) arguments. I have even heard Nigel Farage, leader of UKIP (the most vociferous Leaver) concede in a slip of the tongue moment that Britain might be better off economically inside the EU, but he still argued fiercely for leaving on grounds of immigration fears and that Britain was no longer governable democratically under EU rules. According to his source, 60% of UK laws were not made at home, they were either adopted from Brussels & Strasbourg or are subject to overriding EU legislation.

When we hear such soul-stirring arguments it is worth recalling that the current referendum has historically grown out of a civil war within the Conservative Party. The internecine conflict started shortly before Margaret Thatcher’s resignation at the end of 1990, culminated during John Major’s second premiership from 1992 to 1997 and has only slightly subsided since David Cameron undertook to square the circle inside his party when he became leader of the Conservatives (then in opposition) in 2005.

Some of the cast-iron stalwarts among Conservative Eurosceptic leavers today are John Redwood, Sir Bill Cash, Peter Lilley, Iain Duncan Smith, Nigel Dodds, Dominic Cummings, Theresa Villiers, Lord Lawson, Chris Grayling, Michael Gove and lately Boris Johnson the sparkling tearaway Mayor of London from 2008 to May 2016. The Prime Minister David Cameron, most of his front bench cabinet colleagues, including his Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne as well as former chancellor Ken Clarke and former cabinet minister Lord Heseltine are strong Remainers in the Conservative Party.

Beyond convictions about Europe lie political ambitions. We don’t need conspiracy theories to discover politicking behind the politics. Boris Johnson reputedly prepared eloquent speech scripts both for and against leaving the EU before he had learnt about the prime minister’s decision to openly back the Remain camp and had seen the weak compromises he had achieved in talks with Angela Merkel about EU reform. Johnson probably reckons that taking the position to lead among Conservative Leavers will nudge him closer to the leadership of the Conservative Party once Cameron has resigned (as he announced he would) as leader in 2020 (scheduled time of the next general election) – irrespective of who wins the referendum as the party’s Eurosceptic wing will not disappear. By contrast, George Osborne’s unequivocal stand on Remaining may be fired by a rival ambition to lead the party in the aftermath of the referendum. The dark horse among the unannounced leadership contenders (the “Big Beasts” of the Tory party) is Theresa May, the long serving Home Secretary, whose graduated positions on Europe lend her an air of moderation and calm authority in an otherwise acrimonious debate.

There are few vocal Leavers in the Labour Party: Frank Field, Chairman of the influential House of Commons Work and Pensions Select Committee, senior social and welfare reformer of a moderate political persuasion, is one of the most respectable and prominent among them. Gisela Stuart, the German-born Birmingham MP, who chairs the official “Vote Leave” campaign group, and who has become one the most ardent advocates of Brexit in the last few weeks, is also from Labour. But there is a lingering suspicion that many on the opposite end of ideological spectrum of the Labour Party, the current Corbynite front bench (John McDonell in particular), while paying lip service to staying in the EU, retain a significant whiff of the old (Bennite) Left’s aversion to the EEC. Mick Cash, the new leader of the RMT (Railway, Maritime and Transport Workers) Union, closely allied to Labour, certainly misses no opportunity to argue strongly in favour of leaving.

The fact that both the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition granted permission to their party members to air their views freely in public, thus opening the floodgate to internally divisive speeches and political activity, is testimony to the openness and democratic nature of the debate as well as to the stability of the party political system in the UK. I doubt if this were possible in any country other than the UK. Yet, the open rifts appearing and flourishing within both the main parties may leave wounds behind that could prove hard to heal. Observers disagree whether Cameron will resign as Prime Minister if the Leave campaign wins. He doesn’t have to and this blog writer believes that he won’t. If he will resign that would be because people may consider the referendum to be also a vote on his compromise package negotiated with the EU (i.e. Angela Merkel) before the referendum was announced. Some, like Andrew Lilico, Executive Director of Europe Economics, don’t share my rose tinted view of the aftermath. He reckons in one of his blogs that “Unless there is either a win for Leave in the 2016 EU referendum or Remain wins by 20 per cent plus, it is increasingly difficult to see how most of the current Cabinet who have backed Remain could continue.” Lilico may be right, but I still think he underestimates the general integrity of this campaign.

Where does UKIP stand in all this? UK Independence Party was founded as a single issue organisation aiming at taking the UK out of the Union, so their position is obvious. Yet, the official “Vote Leave” campaign, which mostly contains Tories (but also Labour’s Gisela Stuart and Frank Field), doesn’t wish to hear of admitting UKIP into its ranks, a party that remains tainted by its early association with racial intolerance and crude tactics. In spite of the charismatic personality of UKIP’s leader Nigel Farage, most mainstream politicians wish to remain at arm’s length from the party. While Farage complained about this exclusion in recent interviews with manful indignation in his voice, that will not change the stance of the political establishment.

In the realm of rational arguments the Remain campaign argues that, in addition to becoming isolated and remote from the negotiating tables of the world, leaving the EU would leave the British state £36 billion worse off for every year of not being a member (derived from an official Treasury estimate suggesting that each family would lose £4,300 in income after Brexit). They point out the fallacy of the Leavers’ argument that the UK will save all the £17.8 billion of the UK’s compulsory EU contribution in case of leaving since associated status, EFTA (European Free Trade Association) membership (which the Leavers would presumably like to join) also costs significant amounts. In any case, the £17.8 is in fact £12.9 after the British rebate negotiated by Margaret Thatcher in 1984 has been deducted (at source so it is never actually sent to Brussels in the first place). Furthermore, renegotiating access to the single market would take at least 6 years (estimated from the example of Albania’s experience to negotiate their EU deal). Further still, the European single market comprises 500 million consumers, producing a quarter of the world’s GDP. 45% of Britain’s exports go to the single market. The EU has negotiated 53 trade deals that the UK is a beneficiary of. Britain is an influential member of the European Union with a serious clout at the international negotiating tables, say the Remainers, so talking the EU down amounts to talking Britain down. Can anyone imagine any advantage from leaving this association?

The Leavers counter by asserting that economically the EU is not a free trade area but a customs union, fast developing into full political union, demanding the £17.8 bn membership fee and other endless compliance measures. Significantly, they add that EU regulations add 10-20% to the cost of products across the EU. The UK no longer has its own delegates to a number of world bodies such as the WTO, as the EU delegate now represents all member states. Above all, leaving the union would end the unhindered influx of EU citizens to the UK, which is perhaps the greatest bugbear of the Eurosceptics. Around one million EU citizens migrated and settled in the UK since 2004, while a similar or even larger number of UK nationals are permanently living abroad. The initial complaint against EU migrants was that they are scroungers, taking advantage of the UK’s generous welfare system and that the health and educational infrastructure could not cope with their numbers. In other words, they cost too much money for the UK. When this claim was refuted by solid statistical figures suggesting that EU immigration has produced billions of pounds of wealth for the country, the Leavers (or most of them) turned to the cultural (emotional?) argument: in many urban and suburban settings in the UK, one may leave home, travel to work by train or bus, pop into shops, the newsagent, without hearing one English word spoken. Polish, Romanian, Hungarian drivers, builders, shopkeepers, radio and television stations have taken the place of British ones. This could be an intimidating experience. On one occasion, when Nigel Farage arrived late at a live television show in Wales, he claimed his car had been slowed down on the M4 motorway by a multitude of Polish lorries. (Would Polish lorries no longer roam the trunk roads of the UK after a Brexit?) Former Conservative cabinet minister Peter Lilley argues: “Only if we leave the EU can we regain control of our laws, our money and our borders.” How emotional is that?

Still on emotive territory, the Remainers remind us that European countries had been incessantly at war with each other before integration started after the last war and conjure up the bogey of a Third World War (over Ukraine?) if the Union disintegrates – a process that could be triggered by a British exit. The Schuman declaration promised that integration would make conflict in Europe materially impossible, and look: it has worked! And now Boris Johnson, the most eloquent and literate of the Leavers tells us that the EU’s aims are similar to Hitler’s in trying to conquer Europe. Passions seem to outstrip reason in the Leavers’ camp as we approach the vote. At the opposite end of the spectrum, Hilary Benn (Labour’s shadow foreign secretary) countered in a recent radio debate: “We are not locked in the boot of anybody’s car, we are helping to drive the vehicle.”

It isn't clear whether it helps or damages the Remainers’ cause that some of the most outspoken warnings against voting to leave have come from foreign dignitaries like Christine Lagarde (Managing Director of the IMF), President Obama and the Canadian governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney. In fact there isn’t a single world leader (apart perhaps from President Putin) who would like the UK to leave the EU. The Leavers were particularly galled by Obama’s admonition: “Britain will be at the back of the queue” in trade deals with the US if it leaves the EU. But did the intervention originate with Obama? The Americans never use the word queue (they prefer “line”), so was it Cameron who gave him the “cue”?

And those who accuse Obama of hypocrisy, i.e. that he would never commit his own country to similar limitations of sovereignty, the answer may well be that the limitation had already taken place when the original States of the union combined to form the United States of America where sovereignty was pooled in the greater interest of the whole.

The pot has since been stirred further by Republican presidential hopeful Donald Trump announcing that he would not put Britain to the back of the queue even if the UK votes to leave the EU. If nothing else, the heated exchanges could result in the entry of the word “queue” into the American English vocabulary.

Amidst the cacophony of claims and counterclaims, does anybody remember what Cameron’s negotiations for EU reform were about? People were supposed to have made their stay or leave decisions on that basis. Not much has come of that. Nonetheless, the concessions granted to Cameron are worth recalling at this juncture.

We have just been told that well before the actual talks began Angela Merkel had precluded any discussion of the free movement of EU citizens from the agenda. A no-go area for Germany. Instead, Cameron wrested the following compromises from his EU colleagues: a seven-year freeze on in-work benefits for EU citizens working in the UK; child benefit payments to EU citizens will be indexed to the cost of living according to where the children reside if they are living outside the UK; non-eurozone countries will be able to force a debate among EU leaders about “problem” eurozone laws; and, most significantly, it is now recognised by treaty that “the United Kingdom ... is not committed to further political integration in the European Union ... References to ever-closer union do not apply to the United Kingdom.” All these new clauses will “self-eliminate” if the Leave vote wins on 23 June 2016.

Only a few weeks ago, the Remain camp was leading with a comfortable margin. Today, in the middle of May, with 29% or respondents still undecided, Remain and Leave are head to head in the referendum vote intention poll of polls showing 50-50%. Another poll suggested that 28% of voters will be swayed by “national” considerations, such as migration, while a mere 15% will decide on account of economic reasons. This doesn’t exactly augur terribly well for Britain’s continued membership. There is no reason to be complacent about 23 June 2016 anywhere in Europe.

____________________________________

Az írás a szerző véleményét tartalmazza és semmiképp nem értelmezhető az MTA TK hivatalos állásfoglalásaként.